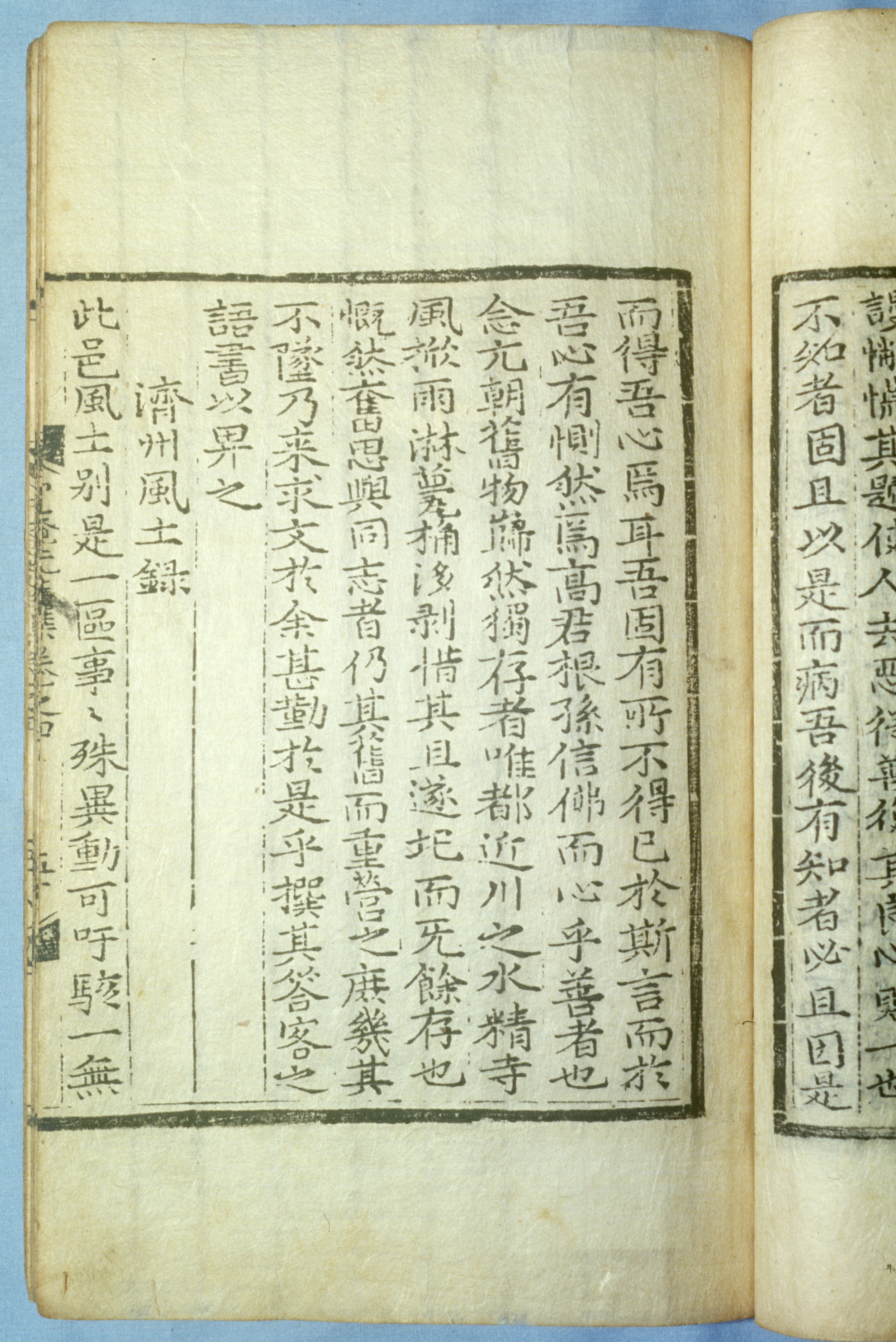

Kim Chŏng, ‘Manners and Nature of Cheju Island’ (Cheju p’ungt’orok’, Ch’ungamjip kw. 4)

Introduction

During the Chosŏn Dynasty, Cheju Island was anything but a vacation spot. For most of the five hundred years of the dynasty, the island was regarded as a harsh, poor, uncultured backwater, its people uncouth followers of strange customs, its climate unpleasant because of the strong winds, and its land infertile. It did not help Cheju's reputation that, due to its remoteness, it also served as a convenient place of exile for disgraced officials. Even being sent to the island as a magistrate was considered a (mild) form of punishment, especially since the passage was dangerous and shipwrecks were not uncommon.1 Having become part of the Korean territory only in Koryŏ times, Cheju was also devoid of places bearing historical significance for the mainlanders. In short, nothing could bring them there but ill fate. Accordingly, knowledge about the island brought back to the mainland remained sparse during the first half of the dynasty; the large majority of extant travel records on Cheju were written after the turn of the seventeenth century.2 This makes Kim Chŏng’s record especially valuable. His description of Cheju Island, while marked by its title3 as a “record”, is in fact a letter that Kim Chŏng wrote during his exile to Cheju, which lasted from 1519 to his death. The text has interlinear auto-commentaries which we have put in parentheses and printed in a smaller font so that it may be distinguished from the main text at one glance, just like the original does. Our own explanations are given in square brackets.

1 A famous case of shipwreck on a return trip from Cheju Island to the mainland was Ch’oe Pu’s 1487 displacement to southern China which he barely survived; his record of his adventures, P’yohaerok, is an important eye-witness account of early Ming China as well as a document of Chinese-Korean relations in the early Chosŏn period. See John Meskill, trl., Ch’oe Pu’s Diary: A Record of Drifting Across the Sea, Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1965.

2 Kim Misŏn lists eleven travel diaries with Cheju as subject, eight of which were written in the 18th and 19th century. See Kim Misŏn, “Sŏm yŏhaeng-ŭl kirok-han Chosŏn sidae kihaeng ilgi”, Tosŏ munhwa 53, 2019, 33-63.

3 The title was presumably added by Kim Chŏng’s great-grandson Kim Sŏngbal who prepared the extant edition of Kim’s Collected Works, printed in 1636.

Translation

Kim Chŏng (1486-1521)

This municipality (ŭp) is by nature and manners a very special place; everything is different, and wherever one goes, one meets with a surprise. There is nothing magnificent to see. The climate is sometimes warm in winter and sometimes cool in summer; it changes all the time without any continuity. The air seems mild but the wind can be piercing. Thus it is difficult to regulate one's food and clothing, and easy to fall ill. Moreover, clouds and fogs create continuous gloom, and the sky seldom clears; violent winds and strange rains spring up at any time, the climate is damp and oppressive. Also, this earth produces a great variety of insects, and especially of flies and mosquitoes. These, as well as all the different worms and bugs like centipedes, ants and earth-worms, don't die in winter, so they are really hard to put up with. I imagine that in the harsh cold of the northern border this nuisance does not exist.4

4 It seems that Kim Chŏng is pondering here the respective harshness of the two remotest places of banishment, the northern border region and Cheju Island.

The living quarters are all thatched; the thatch is not interwoven but just heaped on the roof and pressed down with long beams. Tiled roofs are extremely rare. Even the two prefectural offices of the prefectures Chŏngŭi and Taejŏng are thatched houses. The villages are built spaciously and provide much seclusion. The different wings of a house are not connected to each other. Nobody except the higher officials has floor heating (ondol). They dig holes in the ground and fill them up with stones. Then they cover them with earth in the shape of a heated floor. After it has dried, they sleep on top of it. In my opinion, as this is a windy and moist region, many illnesses like coughs and spitting originate from this.

They abjectly revere shrines and spirits. Male shamans are numerous. They frighten people with disasters and collect riches like dirt. On annual holidays, on the first and the fifteenth day of the moon or on the 'seven-seven' days they sacrifice animals for their heretical temples. Such heretical temples, numbering about three hundred, increase by year and month, and the supernatural deceits are steadily on the rise. When people fall ill, they are afraid of taking medicine, saying that it would offend the ghosts, and they are not enlightened till their death. They customarily have a suspicious fear of snakes. They install them as gods and on every encounter offer them wine and prayers; they do not dare to drive them away or kill them. When I only see a snake from afar, I set out to kill it. The locals at first were greatly alarmed by this. After some time they got used to witnessing it, but believed that I as a foreigner could do it without harm, and did not at all awaken to the fact that snakes have to be killed. Their delusion is really hilarious. I have heard in the past that this place is rich in snakes, and that when it is about to rain the snakes in unison drill their heads through the crevices in the city wall at every spot. When I came here I tried to verify it and found it to be empty words. Snakes are just more numerous than on the continent. This is probably also due to the exaggerated veneration of the locals.

The sound of the people's speech is high and thin, like the pricking of needles, and much of it is unintelligible. Whoever lives here for a longer while naturally understands it. The ancient saying 'the small boys understand the language of the barbarians' refers to this.5 They carry things on the back but not on the head; they have small mortars but no big mills. They beat their clothes but have no stone slab ; they have smelting furnaces but without foot bellows .

5 This "ancient saying" actually is a line from a poem by Du Fu (the fifth of the "Five songs on an autumn plain", Qiu ye wu shou).

6 A local military position of Junior third to Senior sixth rank.

7 A yŏsu led a squad of 125 men.

8 sŏwŏn, a low local office.

9 Yuk Han was dismissed for dishonesty in 1506.

10 mugwi: those serving the spirits.

Besides the local licentiate Kim Yangp'il, there are very few people with some knowledge of literature. Their hearts are vulgar and unthoughtful. From the higher officials down to the humble, all try to contact the influential people at court . The aristocrats among them try to obtain the military position of chinmu6 . The next position in preference is that of officer yŏsu7, and last come the clerks8. The seal-holders and those who studied at the local schools occupy themselves all day with seeking their own profit. From the minutest of disputes they derive bribes, and they lack any idea of honesty and justness. The strong rule over the weak, the violent plunder the righteous. The proclamations of the sovereign do not reach down here; thus it is not surprising that the officials are rapacious like the former Cheju magistrate Yuk Han.9 Those who are honest and just, although being cherished by the common people for their sentiments, are ridiculed by this brand of people as 'off the mark'. If they are not educated with some learning to enlighten their hearts, there is no hope of their ever changing their ways. For their minds are preoccupied with gain and they do not know of anything else. If one talks to them about honesty and justice, they just think it's not profitable and despise it. If a learned monk would use his rhetoric to depict heavens and hells to these people, it might effect something, but the local monks all have wives, live in the village and are dull like trees and stones. Those like the necromancers10 who frighten the people into offerings of cakes and wine also have only their profit in mind.

The three administrative districts i.e. Cheju-mok, Chŏngŭi-hyŏn and Taejŏng-hyŏn are all placed at the foot of Halla Mountain, and the ground is uneven and rocky, with not half an acre of flat land. Plowing it is like picking in a fish-belly. The land looks flat but one cannot see far, as it is so undulating. Though there are mounds, they are disordered and hard to keep apart, the features of the earth being similar to a net, or to a disorderly burial ground. Although there is much accumulated rock , none of them are strange or elegant or in good arrangement; all are dull ores, dreary black and a hateful sight. Although there are hills here and there, they stand lonely, discarded, massive and bald . They lack winding and embracing formations. Only one great mountain rises in the very center, shaped like a vault, but it is merely an obstacle. This is a far cry from your words that 'much bones and little flesh are the appearance of Kŭmgang Mountain'.11 When I think back to the earthy mountains which I have looked down upon before, like when I governed Chŏnŭi and Ch'ŏngju,12 how could I find them here? Also, the mountain's summits are always indented like a pot, and floods of mud accrue in this cavity. All the peaks are like this, so that they are called 'headless mountains' (tumuak). This is especially strange. However, when one climbs the ultimate peak of Halla Mountain, one sees into the blue distance in all four directions, can look up to the 'Old Man' in the extreme south , can point to mountains like Wŏlch'ul in Kangjin-gun, Chŏlla-namdo and Mudŭng near Kwangju, Chŏlla-namdo, and can stir up one's sense for the extraordinary. Li Bo's words "Clouds lower, and the bird roc overturns;/ waves stir, and the sea-turtle said to carry the earth dives under" can be matched with this alone. I regret my confinement and my lack of power. But, having been born as a man to one place, having traversed the great vastness i.e. the ocean, being able to tread this alien region and witness these differing manners is also one of the extraordinary and splendid events in life. For there are those who want to come and cannot attain it, those who want to stay and cannot escape from having to go; this seems to be preordained by fate, how can one struggle with it?

11 The addressee might be a nephew of his. See Hŏ Pong (1551–1588), Haedong yaŏn, "Chungjong sang". The appellation used for Kŭmgang Mountain here is kaegol, literally "all bones". Kim Chŏng had been to Kŭmgang Mountain in 1516, after his release from an earlier exile.

12 In Ch'ungch'ŏng-namdo and Ch'ungch'ŏng-pukto respectively; Kim Chŏng is revered in the shrine of a private academy (sŏwŏn) in Ch'ŏngju.

13 Chŏng-ŭn, silver coins of mediocre quality (about 70% of silver).

14 Such a passage is found in the Bencaojing jizhu by Tao Hongjing (456–536) (but of course it speaks about Koguryŏ, not Chosŏn, thus the place where the high quality omija was to be found according to Tao may have been outside Chosŏn or modern Korean territory).

15 The text gives a Chinese character compound read marŭng and glosses it with the Korean syllable mŏz (머ᇫ). Present Cheju dialect for mŏlkkul is mŏngkkul.

16 In Sinjŭng Tongguk yŏji sŭngnam (1530), kwŏn 38, "Cheju-mok", the muhoemok, which is given as ‘No-ash-wood’ above, is briefly described as follows: "This originates from Udo a small island near Cheju. When being on the sea, it is soft as well as brittle, and drifts on the waves; however, immediately upon leaving the water it becomes hard and solid."

17 We assume that the phrase aeng mu na ya cha 鸚鵡螺椰子 should originally have read 鸚鵡螺 螺椰子, aengmuna being the nautilus and nayaja the coconut. It makes little sense to assume that parrots should have been washed ashore by the sea. On top, the Sinjŭng Tongguk yŏji sŭngnam, loc. cit., also mentions aengmuna as local produce.

18 The names of these two chestnuts (sigayul and chŏngnyul) as well as the Two-years-wood (inyŏnmok) are also given in Sinjŭng Tongguk yŏji sŭngnam, loc. cit., but without any further information.

The region of Halla and the province town have very few fountains or wells. Some village people draw their water from a distance of five li and still call it 'nearby water'. Other fountains give water only once or twice a day and are salty. To draw water, they always carry a wooden bucket on the back to bring home as much water as possible. Moreover, there are very few local specialties. In animals, there are only roe, deer, and pigs in considerable numbers. Besides the badger, which is also numerous, there crows, owls, and sparrows, but no cranes or magpies. Among wild vegetables and herbs, myŏl Houttuynia cordata and bracken are the most common, but 'fragrant vegetables' (ch'wi) Aster scaber, ch'ul Atractylodes japonica, ginseng, tanggwi Angelica acutiloba, and toraji Platycodon grandiflorus do not exist. In sea vegetables they have only seaweeds like miyŏk Undaria pinnatifida, umu known as agar-agar, and ch'ŏnggak Codium fragile, and no laver (kim Porphyra tenera), kamt’ae brown algae, Ecklonia cava, or hwanggak brown variety of Codium fragile. In sweet water fish there are none but those of the 'silver-mouth' Plecoglossus altivelis kind. As for ocean fish, they have abalones Haliotis discus, squid, red horseheads Branchiostegus japonicus, cutlassfish Trichiurus lepturus, mackerels and so on; besides these, the various common breeds like octopuses, male rock-oysters, clams, crabs, herring, sailfin sandfish Arctoscopus japonicus, and croakers do not exist. They produce neither stone products nor ceramics nor brassware; and they have extremely few rice paddies. The local aristocrats eat what they get from trade with the mainland; those who cannot afford this eat grains from dry fields. Thus clear rice wine is very expensive, and summer like winter they drink soju crude liquor. Cattle is plentiful, and they cost no more than three or four lesser-silver coins,13 but in taste they are inferior to those of the mainland, because they feed on wild pastures and do not get any grains. The most ridiculous thing is that they produce no salt although their land is surrounded by the ocean . So they have to import it from Chindo island off Chŏlla-namdo and Haenam peninsula east of Chindo. Thus it is very expensive for ordinary people. Among the local produce, most plentiful is the 'fragrant mushroom' and the fruits of the omija Maximowiczia chinensis which are deep black and as large as fully ripe wild grapes, indistinguishable from the latter. They also taste strong and sweet. The Chinese Herbarium (Bencao)14 says about the omija that 'those growing in Chosŏn are of good quality', and again 'the sweet-tasting are the best'. Now when seeing that the omija fruits growing in our country are purple, small, and sour in taste, and still are prized like this in the Herbarium, then the produce of this place must doubtlessly be the best in the world. Up to now people did not know this and made use of it only to fill their own cups and plates. I was the first to desiccate them; they are extraordinarily rich in flavor. This year, the district magistrate (ŭpchae) and I both gathered a lot and dried them. I intend to send you a little to let you know the taste, but so far they have not completely dried up. Further, there is a wild fruit called mŏlkkul Stauntonia hexaphylla.15 The fruit are the size of a quince; the skin is purple black, and if split open it shows the seeds, which resemble those of the clematis Akebia quinata, but differ in that they are slightly bigger and of slightly richer taste. For they are just a larger kind of clematis. I have heard that they also grow in places on the sea coast like Haenam, but do not know whether this is true. Besides this there are no valuable strange things. The various kinds of fruits of the mainland like pears, dates, persimmons and chestnuts are all extremely rare. Even when occasionally found, they are not delicious. There are absolutely no Korean pine Pinus koraiensis seeds, and pine trees Pinus densiflora are also very rare. The pine needles I take as medicine I have to get from far away. The valuable things of this place are oranges and pomelos, gardenia nuts used for a yellow dye, yew nuts Torreya nucifera, soapberry, logwoods Xylosma congestum, two-years-wood probably an oak species, Quercus glauca, no-ash-wood,16 nautilus shells,17 and coconuts , the more-time-chestnut and the red chestnut ,18 and good horses. They have nine kinds of oranges and pomelos: The golden orange , the milk-tangerine and the Dongting-orange , the green orange , the mountain orange , the tangerine and the pomelo , the Chinese pomelo , and the Japanese orange . All nine kinds have quite similar branches and leaves, only the pomelo is very prickly and the peel of the fruits most fragrant; the tangerine has the thickest leaves, and its peel is least fragrant. This must be the reason they are graded so lowly. All the other kinds are not very thorny , and their leaves are slender; the fruit peel is of strong and not very fragrant odor, but when chewed it has a strong aroma, bitter and hot . One can't bear to eat it, but as medicine it is most effective. This must be the reason that they are graded highly. The trees grow no higher than a little more than ten feet, but the big ones among them look like pillars. They preferably grow in thickets, and their stems and branches are also quite large. As many as ten of them may intertwine like dragons, coiling and lumping together, archaic and tough. The bark of the old trees is yellow and red and covered with moss, that of young ones is dark green, fresh and lovely. The leaves are green throughout all seasons. In this place lacking all worthwhile sights, these groves are really a fascinating attraction.

My living place is half a li away from the eastern gate of the island's capital, on the former site of the Diamond Society Temple.19 I have no neighbors in this very secluded spot. A grass hut of several pillars20 stands there, erected in the style of the north, very bright and spacious. It contains one small room with heating. Outside the living room there's a maru, an open veranda, of the size of half a room, so that I can avail myself of sun- as well as moonlight. Under the eaves of the maru an old persimmon tree with thick foliage spreads its shade. I often sit there on the maru, so close to the tree as to be able to stroke it. The living quarters are enclosed by a stone wall, built of ugly stones which are piled up for more than ten feet; on top of it, wooden railings in the shape of antlers have been attached. The wall is no more than half a p'il roll of cloth away from the eaves. This high and narrow enclosure is in accordance with the state law regulating the abode of exiles. But high and close stone walls are also local custom, serving to ward off violent winds and torrential snows. Moreover, as I am living all alone, I also have to be wary of robbers, so even if I had planned it myself, I would have had to provide this wall; I only wish it were a bit wider. The wall impedes my view and does not allow any aesthetic pleasure. Even to grow plants seems of little interest. Also, I am not in command over the time I spend here; without a sense of a future one has no leisure to concern oneself with gardening. Now that I got your words about having planted a juniper which has grown old by now, my interest has been roused, and I plan to plant, from next spring on, tangerines, oranges, and yews in a row. Straight north from my house, in twenty paces distance from the wall, there is an old pear tree of some ten feet height. It has sparse branches and thin foliage, not a good specimen, but recently it has been trimmed, supplemented with a pavilion, and surrounded by mottled bamboo. As the place is elevated, in the far distance one can see the ocean to the north and the Ch'uja islands a group of islands north of Cheju line up below one's eyes. In the nearer distance, one can see into the town to the west, taking in the rising smoke, the willows around the office buildings and the fruit orchard in the southern city . The orange grove is a very pleasant sight. In the closest vicinity, the orchard of the Diamond Society can be seen, which is full of orange trees. This garden is about fifty to sixty paces removed from my pavilion. It is delimited by a stone wall, but a small bamboo alley leads through. Sometimes I am able to roam beneath those trees among the jade-green leaves and the golden fruit, the green and yellow ripe oranges giving a fragrant feast when cut open. These times are what you have called 'singing long in the woods of oranges and pomelos'. In such times, can I do otherwise but turn my neck in bewilderment and think of you? In this awful place, this pavilion is the one spot where to find some solace.

19 Kŭmgangsa ku sa ki 金剛社舊寺基. A temple named Kŭmgangsa 金剛社 existed in Kŭmhae in Kyŏngsang Province. It is not easy to verify the existence of a temple by the same name in Cheju. A later traveller to Cheju, Kim Songgu (1641-1707, Cheju magistrate 1679-1682), also speaks of this site, in the very same phrasing (Namch’ŏn rok sang, P’arohŏn sŏnsaeng munjip kw. 5, 27b); it is possible that he references Kim Chŏng. Given that “Kŭmgang Society” was also used for Buddhist gatherings, Kim Chŏng might be speaking generically of “a former Buddhist temple”.

20 ‘Pillar’ refers to a unit used for describing the size of houses, ch’ae in modern Korean.

21 Pokch'ŏn-dong is a place near (now in) Pusan well-known for its springs. However, the phrase pok ch'ŏn tong su 福泉洞水 also reminds of the common Daoist appellation for places where the immortals roam, dong tian fu di 洞天福地, so it has connotations of "waters for the immortals".

Also, I luckily live near to a fountain which springs from the eastern corner of the orchard in the southern city. The fountain is very big at its source 21 and flowing out from under the eastern wall, it provides me with water to draw. It is cold as ice, but the lower reaches are impure and unpleasant. When mouthing into the sea, it forms a pool . The silver-lips that breed here can be caught with nets or hooks. One can also fish for various small ocean fish while sitting on the seashore. This would seem quite pleasant but is actually not much fun, a far cry from the pleasures of clear streams and softly flowing brooks. For there is no agreeable place to sit, and fishing in the sea is hindered by the rushing on of winds and waves; on very few days can one settle peacefully, so that no refined atmosphere can come up. Also, as company I have either rustics or Mr. Pang. How could these companions suffice to arouse my enthusiasm? As there is nobody dear to me here to share with, I have almost no heartfelt pleasure, just as you have said. Also, the state law must be respected; thus I seldom go out, not more than once or twice a month, or sometimes not at all for a whole month. Not even to the pear-tree pavilion do I go very often, and still less frequently to the orange garden. To walk alone just increases my musings. . I am separated from my bones and flesh, and anxiously think of my dear ones far away. Of the companions of my roamings in old times, many have already withered away. Forlorn I am in secluded lands, having had to taste the world's inconstancy once more. I am searching for equanimity, and always cheerfully follow the course of things, but when I suddenly think of this, I cannot help being sadly moved.